Updated: April 5, 2015

Five years after the Right to Education Act came into force on April 1, 2010, The Sunday Express visits four schools in four states, not far from the homes of their education ministers, and finds that none strictly conforms to all norms laid out in the Act

5 years later

Bihar, Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan, states The Sunday Express chose for this report, have recorded some of the worst learning levels in recent times. The fourth state, Kerala, is the outlier here. According to the 2014 ASER report, the percentage of Class V children who cannot read a Class II book is 51.9 per cent in Bihar, 53.3 per cent in Rajasthan and 55.3 per cent in UP. Against the national average of 51.9 per cent, Kerala has a far better report card, with only 33.2 per cent of its Class V children unable to read a Class II textbook.

The Right to Education Act, 2009, which came into effect on April 1, 2010, came with two deadlines — March 31, 2013, for full implementation of the Act, and March 31, 2015, to assign trained teachers to maintain Pupil Teacher Ratio. The deadlines have come and gone but most states are nowhere near meeting the RTE norms on playgrounds, boundary walls, toilets for girls, running water, etc. Even the Kerala school did not have a perfect RTE score. The school doesn’t have a boundary wall and the playground is smaller than the minimum 1.5 acres prescribed under the Act

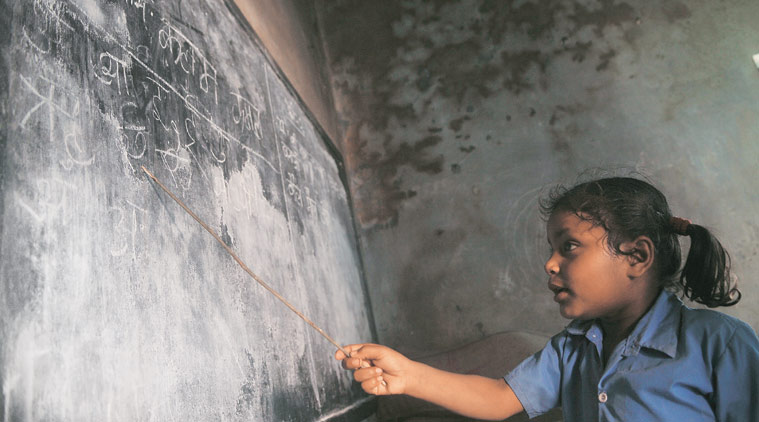

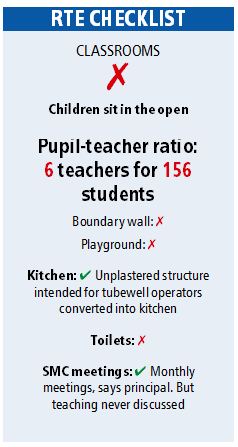

CLASSES UNDER THE SKY

Agaunta village, Siwan, Bihar

Education Minister: P K Shahi

“We are so scared of another mid-day meal tragedy, we cook under a roof even as our students sit in the sun,” says Nitu Kumari, headmistress of the primary school in Hatha, a hamlet in Bihar’s Siwan district.

The 156 students of the school — 122 were shown as present on the day but fewer were actually to be seen — sit in a clearing between Hatha hamlet and its parent village Agaunta. The school is in a palm grove and teachers say falling fruit from the six trees pose a risk. Nearby, in a dilapidated, unplastered one-bedroom structure intended for tubewell operators, their meal is being cooked by three cooks. This then is ‘open schooling’ — everything from classes to lunch happens under the open sky.

Agaunta is the village of Bihar’s Education Minister P K Shahi, a former advocate general of the state, who is now a member of the Legislative Council. Villagers say some of the land surrounding the Hatha school belongs to various relatives of the minister.

There are six teachers, two of them women, in the school that has classes from I to V. All of them are panchayat shikshaks. They were hired by the local self-government and are entitled only to basic government pay.

“We started the school in 2006 when the government decided to have up to three schools attached to each middle school. The idea was to have schools within a kilometre of homes,” says headmistress Kumari.

The government has been unsuccessful in finding land for the school — most of Hatha’s residents are Dalits or Muslims who have small land holdings. So even as Agaunta is set to get a new high school and panchayat bhawan, Hatha’s children sit on the ground, half a kilometre from their hamlet.

Today is the first day of the annual exams — children sit in groups under the shade of trees and write while teachers walk amidst them, supervising. At the end of exam time — which was whenever lunch was ready — a few children shed tears. They wanted more time to write.

Lunch is served at about 12.30 in the afternoon, after the cooks and headmistress Kumari have sampled it, a security feature that was imposed after the 2013 mid-day meal tragedy that claimed the lives of 23 children in the state’s Saran district.

After school winds up at 3 pm, the teachers are supposed to stay on till 4 pm, and the hour is to be utilised to hold bridge classes for weaker students. However, when interviewed separately, teachers had different accounts on the hour. Pravin Rai said they leave by 3.15 pm or shortly after the last child has left, while Vinita Kumari said they hold “remedial classes as they are vital”.

Teachers admit to making the children carry plastic chairs and tables for the staff to the site of the school. “We keep them locked in a room we have rented in Agaunta, along with furniture for a school building, whenever it is built. The children bring it here. What will people think of us as teachers if we carry it on our heads?” asks Rai. Students bring their own empty sacks to sit on the floor.

Two of the six teachers have been trained to be ‘RTE-compliant’ — a diploma course in primary education from IGNOU. There are 17 members in the School Management Committee (SMC) which, according to the Act, has to have parents, teachers, students and local authorities. The headmistress says she organises a meeting at the end of each month. “The problem of land dominates almost every meeting, but our members have no solutions,” says Kumari. “Do we discuss teaching? No.”

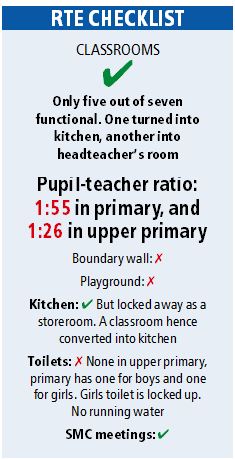

A TOILET BREAK IN THE FIELDS

Gosaipur village, Ballia, UP

Education Minister: Ram Govind Chaudhary

It’s 10.12 am. The annual exam for upper primary students should have started at 10 am, but Preeti Singh and Kumari Aneesa, 10-year-olds in Class VI, are still sweeping the corridor outside their classroom. Neat, clean strokes and the paper wrappings and footwear dust are soon hidden away from view and the girls come running back in, wiping their hands on their skirts.

‘There is no peon in this school and so the students volunteer to help,” says an embarrassed Radha Krishna Ram, the headteacher of the Upper Primary School in Gosaipur village. “This is the minister’s home village and he had flagged off a Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan rally from here on Saturday. There were a lot of people and all this trash is from that day. School was closed on Sunday and we couldn’t clean up. That’s why it’s being done now,” he says.

Gosaipur, the home village of SP leader and Basic Education Minister Ram Govind Chaudhary, is about 420 km from the state capital and is part of Ballia, one of the most backward districts in the state.

The upper primary school is right next to the primary school building. Both schools share a handpump and a kitchen where a gaggle of cooks sits around a cauldron of steaming kadhi, enough for 275 students of the primary school and 104 students of upper primary. A classrooom in the primary school has been converted into the kitchen, while the actual kitchen is now a room to store wood for cooking.

While the upper primary school has no toilet, the primary school has two toilets, only one of which is open. The open one, with ceramic tiles, is for the boys and the male teachers. The women teachers have locked the other one “so it does not get dirty”.

So Sonam Verma, a 15-year-old in Class VIII, goes to the nearby fields whenever she “feels the urge”. “Mushkil to bahut hoti hai, par kya karen (It’s not easy but what do we do)? We go in groups to the fields because my family doesn’t let me go alone,” she says. “First of all, it is embarrassing to go to another school (the primary school building) and ask the teacher for the key in front of everyone. Even if we get the key, the toilet does not have water so we have to fill a bucket from the handpump in the middle of the school, which is even more embarrassing. So we bring bottles of water from home and go to the neighbouring fields during the break,” she says. Her classmate Kumari Amrita adds, “During our monthly periods, we prefer to go home during lunch break and then come back.”

Says Radha Krishna Ram, the headmaster, “The Basic Education Officer has promised a toilet for the upper primary school.”

Sitting in his room in the primary school, headteacher Awadhesh Singh admits there are problems — no running water, not enough classrooms, overstretched staff (five teachers for over 275 students), not enough funds. But there is something he is really proud of: “The minister studied in this school. I studied here too — when the minister was in Class V, I was in Class II.”

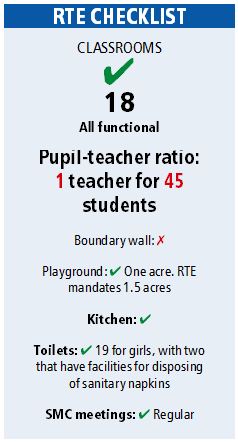

STORIES ON THE WALL

Maithra village, Malappuram, Kerala

Education Minister: P K Abdu rabb

It’s breaktime and the central courtyard at the Government Upper Primary School in Maithra village has just come alive. Under the canopy of two giant mango trees, a group of children plays a game of hopscotch and calls out to each other, girls on bicycles go around in lazy circles, a few boys walk out for a game of football. Inside the classrooms, little girls in headscarves sit chatting. The walls are straight out of a child’s book — a blue sky, a sprawling mango tree, a grinning monkey, a coiled serpent. This school is far removed from many government schools in Kerala and further removed from such schools in many other parts of India.

The Maithra school is part of Malappuram, home to Kerala Education Minister P K Abdu Rabb of the IUML party, that’s part of the Oommen Chandy-led UDF government. Once a district that sent unskilled and semi-skilled workers to Gulf countries, the Muslim-dominated Malappuram has in recent times surged ahead of other districts, its students consistently topping entrance examinations for professional courses.

The Maithra school’s growth chart has somewhat mirrored that of the district. Until a decade ago, the school had fared miserably on most education parameters. But the implementation of a World Bank-aided District Primary Education Programme (DPEP) and the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA) has changed the fortunes of the school, set up back in 1924. If earlier 120 students sat cramped in a dingy classroom, today there are about 42 to 50 students to a room. The school has 635 students from classes I to VII.

“All our students live within 3 km from here and most of them walk to get here. We have one teacher for about 45 students,’’ says headmaster A Haridas.

The computer room, with its deep pink walls, is Muhammed Rashid’s “favourite place in school”. He sits with two of his friends on either side, excitedly jabbing at the screen. The school got a broadband connection five years ago. As the government does not appoint a computer teacher in upper primary schools, the Maithra school uses funds from the School Management Committee to pay computer teacher

K Santhi’s monthly salary of Rs 3,500.

At the rear of the compound are 19 toilets exclusively for girls, with two toilets that have facilities for disposing of sanitary napkins. For boys, there are 16 urinals and four toilets. The school also has a toilet with a ramp meant for physically-challenged students. An overhead tank ensures that the school gets a steady supply of water.

Outside the office room, one of the several rooms around the courtyard, hangs the day’s menu for the mid-day meal – payar (moong), sambar and rice. Besides, each student gets an egg and 300 ml of milk every week.

The new building came up 15 years ago and over the past five years, the school has used SSA funds (Rs 25 lakh in the last eight years) to add several new features — the computer lab, a science lab, a cycling club for girls and vocational courses. Besides, there have been allocations from the local area development funds of IUML MLA P K Basheer and former MP E Ahamed.

Headmaster Haridas says he is proud that there have been no dropouts in recent years. “The school authorities and the members of the local governing body ensure that all children are enrolled in Class I and continue till Class VII. And our teachers enroll their children here instead of sending them to private schools,” he says.

OUT IN THE OPEN

Hathikhera village, Ajmer, Rajasthan

Education Minister: Vasudev Devnani

The harsh summer sun beats down on a group of young school children sitting under a tree. The fidgety students, all of Class IV, keep getting up at intervals to ask for permission to drink water from two taps of potable water. The students are attempting to write a letter in Hindi, but none manages a line beyond the address that has been dictated by the teacher.

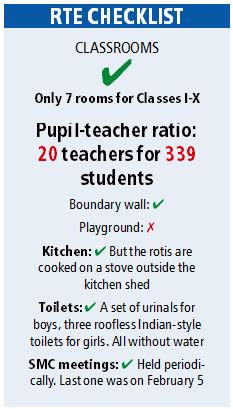

Barely metres away from Education Minister Vasudev Devnani’s residence on Foy Sagar Road on the outskirts of Ajmer city, the Hathikhera Government Secondary School with classes from I to X was set up in 1987 as a primary school. The school was upgraded to senior secondary level this year, but the seven classrooms built in 1987 have remained to house a much larger strength. To tackle the space crunch, the school has chalked out different schedules for the primary and high-school sections. Classes VI to X come in at 7.30 am and leave at 12.30 pm, when the lower classes start and finish by 5.30 pm.

However, now with examinations on for Classes IX and X, the rest of the school has to finish early and make space for the students who come in for the exam by noon. The lower classes, now nudged out of their rooms, have found space in the sultry corridors and under the shade of a tree. Their mid-day meal, a plate of steaming hot dal and rotis, too is eaten in the open.

Teachers in the school point out that the sprawling campus has ample space for a new building to accommodate all its students.

Besides the urinals for boys, a set of three Indian-style toilets, roofless and waterless, stand in a corner next to one that has both — a corrugated sheet for a roof and some running water. This one is for the staff, say students, adding that they do not venture inside the other toilets.

Class IV student Shivani Sain says, “Going to these toilets is scary — anyone could be watching from above. Also the toilets are dry and get clogged. So we just do not go.”

“I am told the last time waterpipes were laid and a Sintex tank was fixed for running water here, they were all stolen by people who scaled the low boundary walls. So now we have a tanker that delivers water every day,” says principal Aruna Rao, who joined a year ago.

Senior teacher Rekha Mathur pulls out registers to show how 12 members attended the last SMC meeting on February 5 but admits that it is after much cajoling that members like Bhag Chand, a milkman and president of the committee for the fourth year running, arrive for these meets.

Bhag Chand, four of whose six children study at the school, says, “Why do I have to come? I get to know what is happening in school through my children.”

Courtesy - Indian Express

0 Comments